Reflections on Time & Mortality, Thomas Stumpf's 2-CD solo recording project, was released February 1, 2017.

from Amazon.com: Pianist Thomas Stumpf is fascinated with the concept of time and how it is utilized to make sense of the human condition. We have language and symbols for time and music is one of the most powerful of those symbols. Stumpf has used this 2-CD recording to reveal composers' concepts of time as it appears in their composition. Time as a straight line -- time as a circle -- time as the tolling of bells -- the totality of time. Music exists in the dimension of time, and is one of the deepest and most genuine expressions of the unity of time. Music offers a deeper satisfaction with its inevitability of beginning, middle, and end that unpredictable real life can't. Moments of deep satisfaction can be found in the works chosen for this recording, especially when listened to again and again.

from Amazon.com: Pianist Thomas Stumpf is fascinated with the concept of time and how it is utilized to make sense of the human condition. We have language and symbols for time and music is one of the most powerful of those symbols. Stumpf has used this 2-CD recording to reveal composers' concepts of time as it appears in their composition. Time as a straight line -- time as a circle -- time as the tolling of bells -- the totality of time. Music exists in the dimension of time, and is one of the deepest and most genuine expressions of the unity of time. Music offers a deeper satisfaction with its inevitability of beginning, middle, and end that unpredictable real life can't. Moments of deep satisfaction can be found in the works chosen for this recording, especially when listened to again and again.

Program Notes

David Fullam: Vernal Pool Looking East and Vernal Pool Looking West

CD 1

John McDonald: Mort, op.519 no.113 [from Piano Album 2013]

Program note by John McDonald:

In Fall 2013, when Thomas Stumpf invited me to contribute some piano music for his recital project “Reflections on Time and Mortality,” I was unsure what form my offering would take. “Time” and “mortality” are rather big topics, so I sought my own smaller way into the endeavor. I found an idea by turning to the O[xford]E[nglish]D[ictionary] to look up “mort” (French for “death,” and the root of “mortality”), uncovering a curious new definition: the note sounded on a horn at the death of a deer. This notion was specific enough for me, and yielded the annunciatory, flexible, yet single-minded first composition in what became a set of autonomous yet interrelated miniatures.

Chopin: Prelude in D flat, op.28 no.15 (1838)

This work is known popularly as the "Raindrop" Prelude, a title derived from a passage in the memoirs of Chopin's lover Armandine Aurore Lucile Dupin (known as George Sand):

"There is one prelude that came to him through an evening of dismal rain... While playing the piano, he saw himself drown in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds... His composition of that night was surely filled with raindrops, resounding clearly on the tiles of the roof, but they had been transformed in his imagination and in his song into tears falling on his heart from the sky."

It is uncertain whether the prelude referred to is in fact op.28 no.15. But it is certain that a constant repeated note sounds throughout the piece - the ticking of the clock, a quiet reminder of our mortality in the lyrical outer sections, a loud and clear reminder of death in the middle section.

Do you hear that clock ticking? Or does the elegant beauty of the melody put you off from hearing anything else and not allow you to understand? Don’t forget: the surface of the music - in this case the fact of its well-known and immediately accessible melody - is never its meaning. There is a ticking clock; and, as the great French pianist Alfred Cortot said of this piece, “Death is there, in the shadows.” It emerges from the shadows in the tragic middle section by that simple reiteration of the beat that is a symbol of the ticking clock, and the ticking clock is a reminder of approaching death. It isn’t morbid because we began with that exquisite melody which comes back at the end. All melody is human song, and the truth that we can let our spirits soar above the inexorable passage of time is one of the things that save us.

John McDonald: Post-Mort, op.519 no. 134 [from Piano Album 2013]

Program note by John McDonald:

A pun on “post-mortem,” this piece came out when I realized I wasn’t quite through addressing Thomas’s request for music. It follows loosely from some of the ideas in Mort, but is much sparer and more inward-looking. At this point I should mention that as Thomas and I discussed the ensuing pieces that spilled out, the idea that they might be interspersed with pieces by other composers (as presented at Thomas' Tufts University recital in October 2014) became a new compositional m.o., as I couldn’t help but write more installments on the mortality subject. The entire set is dedicated to my beloved colleague Thomas Stumpf, a composer/pianist of extraordinary taste, expressive facility, and resilience.

Mozart: Fantasy in D minor, K.397 (1782)

This improvisatory, yet beautifully constructed, work begins with an Andante introduction, a preamble of arpeggios. The first small, dark ripples culminate in a much higher and wider final wave which seems to announce that we are ready for a more conscious emotional exploration. The central Adagio section that follows contains an opening theme of melancholy questioning underlined by an implacably steady heartbeat. The ensuing second theme involves the knocking of fate, followed by anxiety and agitation. Presto outbursts interrupt the sequence of events twice, and the Adagio ends with a return of its opening theme. This "closed" form gives some sense of closure. It suggests that life is not merely a series of unrelated individual events, but that life is a cycle. Events, passages, meanings, return upon themselves and the moments of return are moments of exquisite solace.

The third and final section, marked Allegretto, is sprightlier, livelier than anything that has preceded it. It too has its own closed form (the return of the main theme is exquisitely delayed by a somewhat free, extended cadenza) which only helps to underline its sense of optimism and joy. It hardly seems a stretch to call it a "happy ending."

However, it turns out that the overall form of the Fantasy - an introduction, a slow section in D minor, a fast section in D major - is in an open-ended form, linear rather than cyclic. This is the view of time as an arrow: events strung together more or less loosely in a chronological passage. At its most positive this might indicate a happy-go-lucky attitude. At its most negative it is pessimistic, rooted in the sense that life is random and unpredictable. There is little or no sense of inevitability when we listen to the Fantasy. Were we sure from the start that this particular exploration of the human spirit would end in joy? Is it really joyous laughter in the end, or just a quiet smile, or even a rueful grin? Perhaps just some superficial delight, or a whimsical shrug?

Interestingly enough, Mozart never completed the Fantasy. The commonly played ending was composed by his student August Eberhard Müller for the first edition. For this recording, I have used my own ending. And if you wish to hear the meaning of the Fantasy (as I understand it) changed most radically, listen to the great Mozart pianist Mitsuko Uchida's recording: her ending takes us back to the beginning of the work, to those dark and searching D minor arpeggios, and brings about a melancholy closure.

John McDonald: Post-Post-Mort, op.519 no.136 [from Piano Album 2013]

Program note by John McDonald:

This one is perhaps the bleakest of the five miniatures, and the leanest. However, it is meant to be as sweet as it is desolate.

Bartók: Ostinato [from Mikrokosmos Vol. 6, 1939]

Bartók's Mikrokosmos is a six-volume set of 153 pieces of which Ostinato is the 146th. The title, derived from the Italian for "obstinate," is a musical term for a repeated underlying rhythmic pattern - a concept used in many genres (think riffs and vamps) and in many cultures (the guajeo in Cuba, the lehara in India). Sometimes the repetition is very strict, sometimes - as in Bartók's piece - it is freer and more varied. Here, as in many ostinato-driven musics, it is an elemental life force which powers the extraordinary vitality of the music.

Beethoven: Bagatelles op.119 no.10 and 11 (1820)

The British musicologist Eric Blom wrote of Beethoven's Bagatelles: "They reveal his character more intimately than anything else he ever wrote. They are, if anything in music can be, self-portraits, whereas his larger compositions express not so much personal moods as ideal conceptions... No doubt there is an element of exaggeration in this theory of the difference between composition on a large or small scale, but the fact remains that in the Bagatelles we have some perfect and almost graphically vivid sketches of Beethoven in his changeable daily moods, tender or gently humorous one morning and full of fury, rude buffoonery or ill-temper the next."

The tenth piece of the op.119 bagatelles is most likely the shortest piece of music ever written. Like the Bartók that precedes it on this CD, the bagatelle is driven by a rhythmic ostinato of a kind: constant eighth notes in alternating hands show Beethoven in what another British musicologist, the revered Sir Donald Tovey, called his "unbuttoned" mood.

The eleventh and last piece of op.119 is a complete contrast: calm and contemplative, beginning and ending in chorale-like simplicity.

John McDonald: Barque, op.541 no.7 [from Piano Album 2014]

Program note by John McDonald:

Composed early in 2014, Barque (meaning “sailing vessel”) alludes to the barcarolle, a form used in piano miniatures by Mendelssohn and Chopin in particular and indicative of the rhythm of the Venetian gondoliers’ stroke (typically in a 6/8 meter; my piece alternates 6/4 and 9/4). I think of this piece as the ferryman Charon’s oar-strokes as he carries the newly deceased across the River Styx to the underworld - or as any such similar image that may come to the listener’s mind.

Rakhmaninov: Prelude op.32 no.10 (1910)

Rakhmaninov composed the 13 Preludes op.32 in 1910. Their keys ensured that he had written 24 Preludes in all major and minor keys, as Bach (twice over!) and Chopin before him.

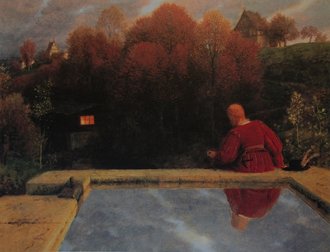

Rakhmaninov was one of the greatest pianists of his time, and occasionally wrote piano pieces which seem primarily designed to show off. His greatest works, however, contain a strain of dark melancholy and a supremely Russian fatalism that gives them extraordinary emotional richness. This prelude certainly belongs to the latter category, and was the composer's personal favorite. In composing it he was inspired by the Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin's work Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming"):

Schubert: Moment Musical D.780 no.2 (1823-28?)

Schubert's Moments Musicaux are among the most performed of his piano pieces. A number of them - and certainly this one - are rather longer and of greater depth of feeling than their title might indicate.

This work alternates between a largely chordal A flat major section, whose main thematic material has the unusual characteristic of coming to a halt on the second beat of the measure. This quiet, contemplative music alternates with F sharp minor sections which have flowing triplet figures in the left hand and are much more explicit in their emotional drama.

The juxtaposition of this piece with the Rakhmaninov Prelude which precedes it on this CD is at least in part motivated by the fact that the opening motifs of both works are based on precisely the same rhythm.

John McDonald: Mere Mort, op. 541 no.36 [from Piano Album 2014]

Program note by John McDonald:

The title: as in “mere mortal”. This final phase in the series of five is unforgiving and forthright, yet includes a tender passage (as in Post-Post-Mort) that might suggest a miniature life-death process devoid of beginning or end.

Janáček: Dobrou noc! (Good Night) and V pláči (In Tears) [from Po zarostlém chodníčku (On an overgrown path), 1911]

The years 1904-1916 were overshadowed for Janáček not only by the fact that the Prague opera house rejected his operatic masterpiece Jenufa (1904), but by the death of his daughter Olga and the virtual dissolution of his marriage. However, these years also produced a number of masterpieces, including the fifteen short piano pieces entitled On an overgrown path. Like so much of his music they are marked by an unusual combination of the expressionistic quality of their often highly charged emotional content and the impressionistic quality of their unique harmonic and textural language.

Gregory W. Brown: Sweet & Twenty (2011)

Program note by Gregory W. Brown:

Sweet & Twenty was originally scored for solo guitar, here rewritten for piano. It was premiered alongside Leoš Janáček’s “Dobrou noc!” [Good Night!] from On an Overgrown Path. The two works have some commonalities that will be obvious to the listener, as Sweet & Twenty alludes quite clearly to the delightful “Dobrou noc!”

Sweet & Twenty also subtly references Janáček’s second string quartet, "Intimate Letters," which is a passionate musical plea to a much younger woman. The title is a reference to Feste’s song O Mistress Mine from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

What is love, 'tis not hereafter,

Present mirth, hath present laughter:

What's to come, is still unsure.

In delay there lies no plenty,

Then come kiss me sweet and twenty:

Youth's a stuff will not endure.

Thomas Stumpf: The Spirit and the Dust (2014)

This work is a set of variations, though their ordering is eccentric: the theme appears in the middle of the piece, after an introduction and the first two variations; it is followed by two further variations and a short epilogue.

The melody is derived from a 1970 song by the German singer-songwriter Reinhard Mey entitled Schade daß du gehen mußt (It's a pity that you have to go). The words tell of a friend who has died too soon; their wistful melancholy is only occasionally charged with a little bitterness: "You who today will see the one who guides our path, ask him this non-binding question: what was he thinking?" I first heard this song a few years after the death of my brother at age 22 (when I was 18), and its simple, haunting beauty has stayed with me ever since.

The title is taken from the following poem by Emily Dickinson:

Death is a Dialogue between

The Spirit and the Dust.

"Dissolve" says Death -- The Spirit "Sir

I have another Trust" --

Death doubts it -- Argues from the Ground --

The Spirit turns away

Just laying off for evidence

An Overcoat of Clay.

Schubert: Andante from the Sonata in A major D.664 (1819)

The theme of this movement contains what is for Schubert a not atypical, emotionally ambiguous mixture of tenderness and deep yearning. He used some of the same musical material at the beginning of a song he wrote two years later (in 1821, D713b): a setting of a poem by his friend the Austrian novelist Caroline von Pichler entitled Der Unglückliche (The Unhappy One). In the song this material is associated with sleep, a gentle metaphor for death:

Die Nacht bricht an, mit leisen Lüften sinket

Sie auf die müden Sterblichen herab;

Der sanfte Schlaf, des Todes Bruder, winket,

Und legt sie freundlich in ihr täglich Grab.

[Night approaches, with gentle breezes it sinks

Down upon the tired mortals;

Gentle sleep, brother of death, beckons

And lays them gently in their daily grave.]

Mozart: Minuet in D major K.355/576b (1789-90?)

Late in his all-too-short life, Mozart explored new territories in his musical language - perhaps partly inspired by his encounter with the works of J. S. Bach, perhaps also simply by his own deeply personal need to open up his music to new emotional territory. This short Minuet - for which he never wrote a Trio, and which my teacher Ernst Oster believed was not completed by Mozart even in its Trio-less form - is such an exploration. In The Compleat Mozart, Neal Zaslow writes of "its chromaticism, its audacious harmonies, and the extraordinary contrasts it is able to express within a single page." The result is a miniature masterpiece of ineffable poignancy.

It appears on this CD because of its beauty and also because it is, among all the hundreds of pieces I have performed during my long and checkered career, my wife Holly's favorite.

John McDonald: Temp, op.541, no.94 [from Piano Album 2014]

Program note by John McDonald:

An afterthought-as-gift for pianist/composer Thomas Stumpf and the sixth piece in the set of “mortality miniatures” tailored for Thomas, Temp (as in both “temporal” and “temporary”) reflects yet again on the reflections brought to the surface by Stumpf’s artistry. Postlude-like, I can imagine it being performed as either a temporary conclusion (benediction?) or a kernel for new pianistic thinking.

CD 2

Rebecca Sacks: One at a time (2015)

Program note by Rebecca Sacks:

This composition was written for Thomas Stumpf, specifically for this recording, and is dedicated to him with heartfelt gratitude and admiration.

The piece is called One at a Time because it consists exclusively of arpeggios, so only one note is played at a time, with no block chords or simultaneous attacks throughout.

The title also relates to my own reflections on time, and how I try to spend the moments in my life. Over the past fifteen years, I have studied mindfulness meditation, which emphasizes living in the present moment with kindness. Tara Brach, my meditation teacher, has been an inspiration as I wrote this piece, and I would like to thank her for helping me to cultivate the ability to live one moment at a time.

Scott Joplin: Solace (1909)

Ever since George Roy Hill's 1973 movie "The Sting" popularized the ragtime music of Scott Joplin (the film's soundtrack, constructed by Marvin Hamlisch, included Solace), it is heard frequently and in many different guises.

As a boy, Joplin studied with a German music teacher named Julius Weiss, who was clearly a major influence. Joplin wanted his compositions to be performed as written, without improvisation, and he always hoped that his piano pieces would take their place alongside the character pieces of Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schumann, et al.. Joplin historian Bill Ryerson wrote: "Joplin did for the rag what Chopin did for the mazurka. His style ranged from tones of torment to stunning serenades that incorporated the bolero and the tango."

Solace is subtitled "A Mexican Serenade," and is marked to be played in "very slow march time."

Bartók: Bagatelles op.6 nos.2, 3 and 6 (1908)

In the last year of his life, Bartók wrote of his relatively early Bagatelles: "A new piano style appears as a reaction to the exuberance of the romantic piano music of the nineteenth century, a style stripped of all unessential decorative elements, using only the most restricted technical means." At the same time it should be noted that the Bagatelles were composed shortly after Bartók's heart had been broken when the famous Hungarian violinist Stefi Geyer had ended their relationship (the last two of the thirteen Bagatelles refer directly to this event).

As in Bartók's Ostinato (see CD1), many of the Bagatelles use repeated underlying rhythmic patterns. In Bagatelle no.2, the repetitive pattern is free and varied and drives the comedic energy of the music. In the right-hand figures of the third Bagatelle, the repetition is startlingly strict and unvaried. Bagatelle no.6 has no impulse that we would normally call an ostinato: it is an exquisitely lyrical piece. But its deceptively simple and repetitive rhythm gives it a similar kind of inevitability, though here the emotional result is one of deep melancholy.

Chopin: Preludes op.28 nos.9 and 14 (1838)

I have juxtaposed these two Preludes because they become, in my conception, a miniature version of the final two movements of Chopin's Piano Sonata no.2: a funeral march followed by a perpetuum mobile (a piece literally in perpetual motion). Is the funeral march an expression of grief, or of anger, or of the triumph of the human spirit over death? Is the perpetuum mobile, as Arthur Rubinstein described it, the "wind howling around the gravestones"? Could it be an expression of rage or of despair? Or was James Huneker correct in asserting that Chopin called it two hands "gossiping in unison after the March"?

Perhaps these pieces are best heard without reference to any such verbal descriptions. No matter how you hear them, they express powerful emotions in small, explosive packages.

Yehudi Wyner: Delirium breve [from the New Fantasies, 1991]

From the Composer's Note in the published edition of his Fantasies for Piano:

"The New Fantasies (1991) are shards from the kiln, so to speak. While at the American Academy in Rome as Composer-in-Residence for the spring of 1991, I was completing a piece for the Boston Symphony Chamber Players and another for Da Capo, the New York based chamber ensemble. The inexorable deadlines seemed to be approaching with increasing speed and I needed to work with total concentration. Outside diversions were few, but inner digressions proliferated. Some grew directly out of the work I was doing, a close examination of a chord progression, a series, a sonority. Other materials were altogether unrelated, unwelcome intruders on what I thought needed to be an exclusively focused context. If the unbidden visitors chose to stay, indeed obsessed me with their annoying insistence, I had no choice but to acknowledge them, taste and better judgement notwithstanding, and to listen to what they had to say. At a certain stage in our work the suspension of judgement may be the most important strategy we can embrace in order to liberate the unsuspected layers of our creative thought."

Delirium breve is dedicated to the Canadian abstract painter Dorothea Rockburne, whose art draws much of its inspiration from mathematics and astronomy.

Janáček: Lístek odvanuty (A Blown-away Leaf)

[from Po zarostlém chodníčku (On an overgrown path), 1911]

For notes on Janáček's On an overgrown path, see above.

Debussy: ...feuilles mortes

[from Preludes Book 2, 1912]

Debussy: ...des pas sur la neige

[from Preludes Book 1, 1910]

Debussy wrote 24 Preludes: a first book of twelve in 1909-10, the second 1912-13. Debussy attached titles to his pieces, though these titles are written at the end of each score and Debussy himself warned against taking them too literally.

These two Preludes (translated: ...dead leaves, and ...footsteps in the snow) may not be literally autumnal and wintry, but their mood most certainly is. The second of them is unusual for its specific expressive indications in the score: of the opening motif Debussy writes "Ce rythme doit avoir la valeur sonore d'un fond de paysage triste et glacé" (This rhythm should have the sonority of a sad and frozen landscape in the background) and a melodic fragment towards the end is to be played "Comme un tendre et triste regret" (Like a tender and melancholy regret).

J. S. Bach: Andante from the Italian Concerto, BWV 971 (publ. 1735)

Bach's Italian Concerto is originally entitled "Concerto nach Italienischem Gusto" (Concerto according to Italian taste). The Concertos of 18th century Italy relied on different sizes of ensembles within an orchestra for dynamic and textural contrast. Bach used the two manuals of the harpsichord to achieve a similar effect; on the modern piano, dynamic differentiation takes the place of the two manuals.

The slow movement of the Concerto is written to be played with the right hand on the forte manual and the left hand on the piano manual throughout. The long-lined, exquisitely decorated melodic contours of the right hand are juxtaposed with a quiet, relentless ostinato figure in the left hand.

Hayes Biggs: "The secret that silent Lazarus would not reveal" (Prelude no. 1, after Billy Collins' "The Afterlife", 2015)

Program note by Hayes Biggs:

The secret that silent Lazarus would not reveal takes its title from a poem by Billy Collins, which I found helpful in my own struggles with the concept of an afterlife.

“While you are preparing for sleep, brushing your teeth, or riffling through a magazine in bed,” he writes, “the dead of the day are setting out on their journey. They’re moving off in all imaginable directions, each according to his own private belief...”

Lazarus’s secret, Collins reveals, is that “you go to the place you always thought you would go, The place you kept lit in an alcove in your head.” He gives examples, including “standing naked before a forbidding judge who sits with a golden ladder on one side, a coal chute on the other” to “approaching the apartment of the female God, a woman in her forties with short wiry hair and glasses hanging from her neck by a string.”

Despite, or perhaps because of my hellfire-and-damnation-filled Baptist upbringing, I found this whimsical poem oddly reassuring. Commissioned by Thomas Stumpf, this short prelude imagines a kind of jazzy march of the motley parade participants, tinged with hints of blues and gospel.

Chopin: Prelude op.28 nr.17 [1838]

From the memoirs of the great Polish pianist-composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski:

"[Chopin's student] Mme. Dubois said that Chopin himself used to play that bass note in the final section [of Prelude no.17] with great strength. He always struck that note in the same way and with the same strength, because of the meaning he attached to it. He accentuated that bass note - he proclaimed it, because the idea of that prelude is based on the sound of an old clock in the castle... Chopin always insisted the bass note should be struck with the same strength - no diminuendo, because the clock knows no diminuendo."

Debussy: ...la cathédrale engloutie [from Preludes Book 1, 1910]

The legend behind this Prelude (translated: ...the sunken cathedral):

The city of Ys was built below sea level by King Gradlon at the request of his daughter Dahut, who loved the sea. It became the most beautiful and impressive city in Europe, but also a city of sin: Dahut organized orgies and habitually killed her lovers when morning broke. Saint Winwaloe warned of God's wrath and impending punishment, but he was ignored.

One day, a knight dressed in red came to Ys. Dahut asked him to leave Ys with her, and finally one night he agreed. A storm broke out in the middle of the night and the turbulent waves smashed against the walls. Dahut said to the knight: "Let the storm rage. The city gates are strong, and my father the King owns the only key." The knight replied: "Your father sleeps. You can easily take his key." So Dahut stole the key and gave it to the knight, who was none other than the devil himself.

When the devil opened the gate, a wave as high as a mountain collapsed on Ys. King Gradlon grabbed Dahut and climbed on his magic horse. Saint Winwaloe shouted to him: "Let go the demon sitting behind you!" Reluctantly Gradlon pushed his daughter into the sea. The waves swallowed Dahut, who became a mermaid.

It is believed that the bells of the sunken cathedral of Ys can still be heard when the sea is calm.

[My performance of this prelude is based on the new Durand Edition that takes into account Debussy's own piano-roll performances.]

Enescu: Carillon-Nocturne [from Suite op.18, 1916]

Enescu was one of the greatest Romanian musicians of the 20th century; as a composer he was much influenced by his native folk music and by far his best known works are the Romanian Rhapsodies. Although he was an accomplished pianist (much admired by the great French pianist Alfred Cortot) he wrote few piano pieces that are still performed today. The Carillon-Nocturne from his third Suite is remarkable for its evocation of the sound of clanging bells, high and low, distant and ear-splittingly present: a masterpiece of pianistic impressionism.

Yehudi Wyner: L'auberge de l'Ill (1993) [from the Post Fantasies]

In his note on this fantasy, Yehudi Wyner wrote: "This began as a song evoking the memory of an exquisite restaurant in Alsace. The song was conceived as part of a song cycle entitled "Restaurants, Wines, Bistros, Shrines," celebrating outstanding dining experiences shared with friends in France and Italy. While the words "L'Auberge de l'Ill" suggested the music for the beginning of the song, the music rapidly developed on its own, leaving the text far behind, and I found myself unable to invent a convincing continuation to the text. So, alternatively, the song became a piano piece, aspiring to become a song."

From a long conversation with the composer, I discovered that the structure of this piece derives from Kaneto Shindo's 1960 movie "The Naked Island," which describes the oppressed life of a poor farming family. The very contained aesthetic suddenly breaks out into an emotional explosion of anguish upon the death of one of the characters.

Yehudi Wyner: Sixty points of light (1993) [from the Post Fantasies]

In his note on this fantasy, Yehudi Wyner wrote: "Sixty Points of Light was composed for Michael Putnam, Professor of Classics at Brown University, as a greeting on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. I imagined the archangel Michael dispatching sixty of his legions to fight the devil."

This composition, like so many others on these CDs, contains the motif of the ticking of the clock. Relentless, implacable quarter notes dominate the rhythm. The harmonic language is rich in its non-tonality: all the more surprising that the piece resolves gradually to a pianissimo C major chord at its conclusion. An acceptance, perhaps, of the relentless passage of time: an acceptance that might well be appropriate on the occasion of a sixtieth birthday.

Mozart: Fantasy in C minor, K.475 (1785)

This Fantasy is the longest and the most daring of Mozart's individual piano pieces. It begins with a deep and dark Adagio in C minor, which moves, by way of one of the many exquisite transitional passages in this piece, to a lyrical section in D major. This in turn gives way to an Allegro which starts dramatically in A minor and then incorporates another lyrical section, this time in F major/minor. A transition brings us to an Andantino of quiet, short and broken statements repeated over the entire range of Mozart's keyboard. This is followed by a dramatic outburst in G minor. Just when we feel certain that this Fantasy is in the same kind of linear mode as the D minor Fantasy (see CD1), i.e. that life is a confusing sequence of only sporadically related events, a long transition leads to a breathtakingly unexpected return of the opening Adagio. Life in the form of a cycle after all, but I am uncertain how much consolation it brings in this instance. The work ends inconclusively with an uprushing C minor scale. Perhaps this is a shaking of our fists at the injustice of the gods - but it certainly leaves us dangling with a question mark over our heads.

A question mark seems to me the most appropriate way to end these CDs.

Enescu was one of the greatest Romanian musicians of the 20th century; as a composer he was much influenced by his native folk music and by far his best known works are the Romanian Rhapsodies. Although he was an accomplished pianist (much admired by the great French pianist Alfred Cortot) he wrote few piano pieces that are still performed today. The Carillon-Nocturne from his third Suite is remarkable for its evocation of the sound of clanging bells, high and low, distant and ear-splittingly present: a masterpiece of pianistic impressionism.

Yehudi Wyner: L'auberge de l'Ill (1993) [from the Post Fantasies]

In his note on this fantasy, Yehudi Wyner wrote: "This began as a song evoking the memory of an exquisite restaurant in Alsace. The song was conceived as part of a song cycle entitled "Restaurants, Wines, Bistros, Shrines," celebrating outstanding dining experiences shared with friends in France and Italy. While the words "L'Auberge de l'Ill" suggested the music for the beginning of the song, the music rapidly developed on its own, leaving the text far behind, and I found myself unable to invent a convincing continuation to the text. So, alternatively, the song became a piano piece, aspiring to become a song."

From a long conversation with the composer, I discovered that the structure of this piece derives from Kaneto Shindo's 1960 movie "The Naked Island," which describes the oppressed life of a poor farming family. The very contained aesthetic suddenly breaks out into an emotional explosion of anguish upon the death of one of the characters.

Yehudi Wyner: Sixty points of light (1993) [from the Post Fantasies]

In his note on this fantasy, Yehudi Wyner wrote: "Sixty Points of Light was composed for Michael Putnam, Professor of Classics at Brown University, as a greeting on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. I imagined the archangel Michael dispatching sixty of his legions to fight the devil."

This composition, like so many others on these CDs, contains the motif of the ticking of the clock. Relentless, implacable quarter notes dominate the rhythm. The harmonic language is rich in its non-tonality: all the more surprising that the piece resolves gradually to a pianissimo C major chord at its conclusion. An acceptance, perhaps, of the relentless passage of time: an acceptance that might well be appropriate on the occasion of a sixtieth birthday.

Mozart: Fantasy in C minor, K.475 (1785)

This Fantasy is the longest and the most daring of Mozart's individual piano pieces. It begins with a deep and dark Adagio in C minor, which moves, by way of one of the many exquisite transitional passages in this piece, to a lyrical section in D major. This in turn gives way to an Allegro which starts dramatically in A minor and then incorporates another lyrical section, this time in F major/minor. A transition brings us to an Andantino of quiet, short and broken statements repeated over the entire range of Mozart's keyboard. This is followed by a dramatic outburst in G minor. Just when we feel certain that this Fantasy is in the same kind of linear mode as the D minor Fantasy (see CD1), i.e. that life is a confusing sequence of only sporadically related events, a long transition leads to a breathtakingly unexpected return of the opening Adagio. Life in the form of a cycle after all, but I am uncertain how much consolation it brings in this instance. The work ends inconclusively with an uprushing C minor scale. Perhaps this is a shaking of our fists at the injustice of the gods - but it certainly leaves us dangling with a question mark over our heads.

A question mark seems to me the most appropriate way to end these CDs.